CRASHING ON TAKEOFF

In the autumn of 2015 in Lviv, I attended a four-day training course with business coach Alexander Friedman. I returned inspired and motivated to work on the company structure. By spring, I had formed a team of eight seniour managers and sent them, too, to study with Friedman. For two years, we were hard at implementing all kinds of changes.

Then I ended up firing five out of eight of these managers. On top of that, to support the new structure in anticipation of the ramp up in production we hired fifty-two people.

Two years later, on the eve of the crisis, we cut fifty!And.... Nothing had changed: neither the quantity nor the quality of theproducts, nor the delivery times...

My sunk labor costs during this periodamounted to about 24 million hryvnias. They were even higher if you add thecost of training, team building, and strategy sessions.

“What went wrong?” I asked myself whilecalculating my losses. Why didn't this project take off, and why do goodinitiatives fail in general so often?

Here are the reasons I came up with:

Uncalled for "betterments". I remember that during the training Friedman said that business is prone to two crises: crisis of growth and crisis of bureaucracy. If you see that one of them is approaching and you do nothing, the company is doomed. In 2015, PET Technologies had 270 employees, and the company was flexible and efficient. But, fearing a growth crisis, I decided to act proactively. As a result, we caught the bureaucracy crisis. When we created the "right" departments, there were so many managers that meetings lasted up to three hours, while their effectiveness approached zero. Not a private company, but a government agency!

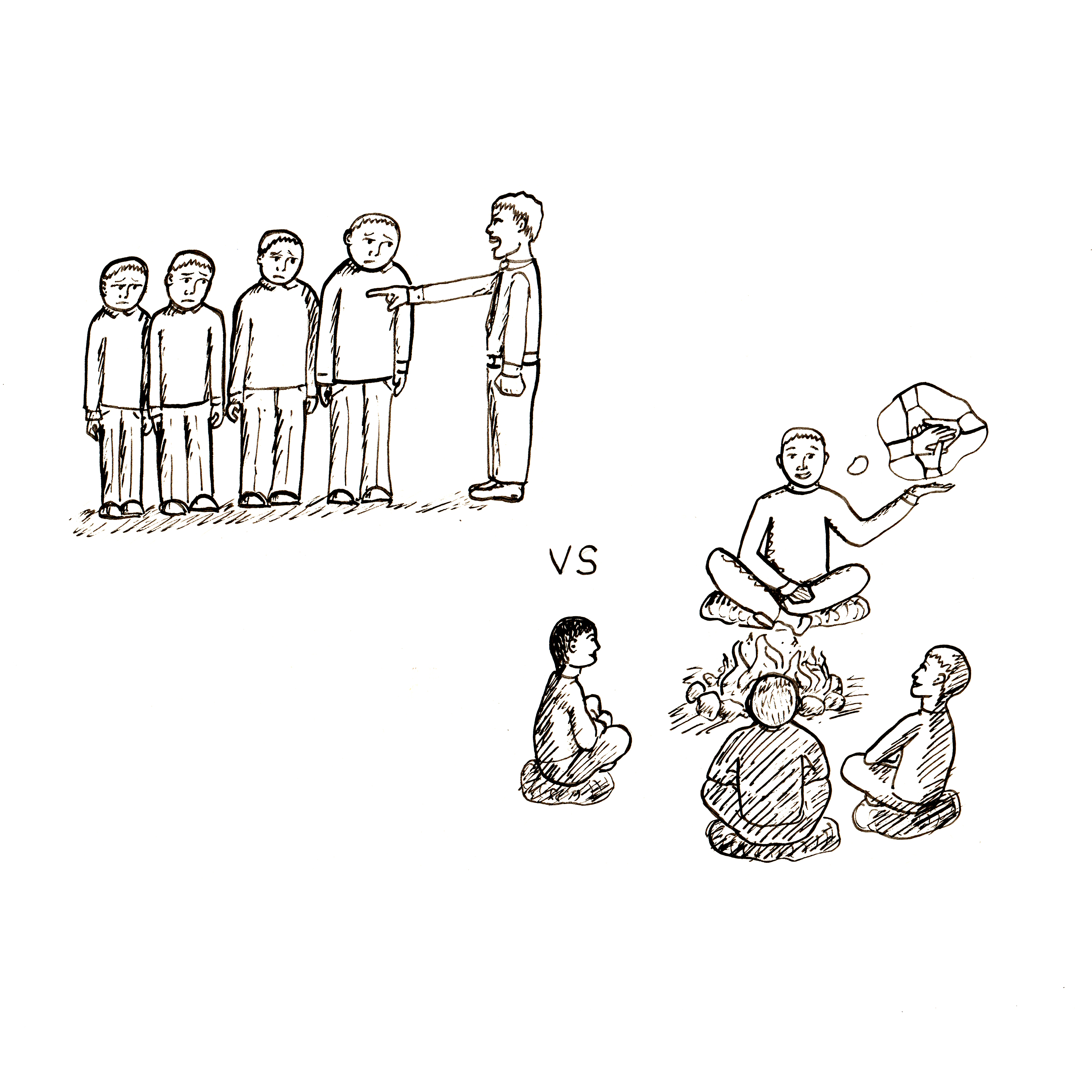

Changes at the owner's whim. Sometimes you read, hear, see something at your neighbor’s, get excited, and decide to implement that same thing right away. I am sure you are familiar with "agile”, "kaizen", “oaken”, "lean" and other initiatives that stalled on takeoff. Perhaps you know them from experience. When changes are viewed as “fun” instead of the pre-conditions of the company’s existence, the owner quickly cools off, loses interest, and delegates. A company that has been operating for 15-20 years is an established system that seeks stability. Seeing danger in everything new and rejecting changes is natural. If you initiated changes and assigned responsibilities but then “went fishing” for a couple of weeks, rest assured - everything will come to a grinding halt even before it begins.

Internal destructors.Have you, as the founder of a company, ever heard the phrase "It won't work for us” from one of your subordinates? And you can't help but ask, "Excuse me, who is ‘us’?" In those moments, you feel like a guest in your own business. It turns out that there are those who know better what will work and what won’t. Often, these are the old-timers who were with you when you started your business. I call them the officer corps. These people can be both a reliable support and defense line for the owner, and the key destructive factor. These are informal leaders who feel the mood of the team and know how to give effective resistance to any changes. If the team, led by them, kills your initiative even one time, they become stronger. Next time they will have a strong reason to say, "We've been through this before." Your leadership team tries to protect you from issues, but if they feel threatened by your initiatives, they will create work and throw several weeks’ worth of problems at you. That's how the system works. And the older and more cohesive the team is, the harder it is to push through changes.

How to level off with these three reasons? Onesolution is to invite external consultants! No matter how brilliant the owneris, he cannot adequately assess the state of his company and see all itsproblems. A fresh look at your old kitchen is worth paying for. They willconduct a diagnostic and determine what changes, if any, the company needs. Andif they are needed, which and to solve what problems? And then, once hired forthe project, they will be able to competently structure it, impartially andpainlessly eliminating toxic employees, including the old-timers that the ownerwould not dare to touch. I experienced this myself. I invitedconsultants twice, in 2009 and in 2015. First time we wanted to create a properstructure for the business to contain early signs of internal chaos. This is astate that any growing business built from scratch goes through at a certainstage. Consultants immediately asked me for a list of 10 key employees of thecompany.

They conducted two-hour conversations witheach of them, asking questions that brought some veterans with "unshakablepositions" to their wit's end. From what I remember, the questionswere “how and in what form do you report on the work done”? How do you controlthe transfer of tasks further along the chain in the business process? I didnot ask my employees such questions, because I did not even know that theycould be asked! After a series of interviews, they singled out two people theyrecommended I fire because of how toxic they were. I didn't do it and came toregret it later. Anyhow, they left the company a few years later.

In 2015, we planned to double production, andto create an appropriate structure and increase staff for that task. Theconsultants did everything right, we hired 52 people, created eightdepartments, each with its own manager. However, the market situation at thattime did not favor our growth plans. In addition, we got bogged down inbureaucracy. Inefficient meetings, lengthy approvals for every littlething. And when I heard that my super diligent and responsible people did notdo their job because it was not in the regulations, I realized - it wasn'tflying.

Hence rule number two: processes should flow.As soon as you feel that a process is starting to stall, discard it. Bureaucratization of a growing company is a necessary step. But if it starts tohinder the work, you need to simplify it and partially (not completely) abandonit. In our case, expectations were not met also for external reasons, thegrowth in production was not economically justified, so out of the 52 hiredemployees, we fired 50 after two years. I disbanded the departmentsleaving only three directors, and for more than two years now, the company hasbeen working perfectly. Issues are resolved quickly, and even our quarterlymeetings do not last more than 45 minutes. The consultants' contributionwas very valuable because they helped us implement the structure, identifyuseless and toxic people, and taught us many tricks that are not taught incollege or MBA programs.

If you get an urge to change and improve,first honestly ask yourself a question: is it really necessary, or are youbored and looking for something to do? If it's the latter, don't mess with youror others’ brains. Do something useful to blow off steam.

However, if changes are necessary and thebenefits to the business are obvious, then act. But go all out, controlevery step, create new rules, and make sure that everyone plays by them withoutexception. Without a compelling reason, external expertise, a big cleanup, andthe unwavering will of the owner, nothing will work.

I do not consider my own experiment withstructuring the company a management mistake. This is a vaccination againstfuture imbalances. Having paid a high price, I succeeded in optimizing andbalancing the system. Most importantly, these moments reveal the most dedicatedemployees who will then become a reliable backbone of stable operations and forimplementing future changes.